Fear and Loathing in Public Health, Part 2

Following Part 1, here I will discuss the remainder of Chapman’s (2018) editorial regarding

the historical review by Fairchild and colleagues (2018).

“A Perverse Ethics”

In the final section of his editorial, Chapman addresses the question “is it unethical to upset?” He concludes in part with

this statement:

It is a perverse ethics that sees it as virtuous to keep powerful, life-changing information away from the community simply because it upsets some people.

It should be unsurprising from my preceding discussion that I find this to

be simplistic rhetoric, and in this section Chapman makes several statements I find questionable. I shall examine them here.

Chapman: “Why is the goal of avoiding any communication that might make people feel uncomfortable or self-questioning

self-evidently a noble, ethical criterion in the ethical assessment of public health communication?”

Phelan: I think the best answer is the one to which Chapman wishes to lead us: it simply is not. I do not think

this answer follows from a more general assertion that public campaigns should not be concerned with emotional or

psychological harms of FMC at all, but rather that it is nearly ensured by Chapman’s construction of the question.

Like C5, the proposed criterion is simply untenable at face value.

Chapman: “Although rendering vivid the carnage and misery caused by speed and intoxicated driving may upset some who

are quadriplegic, how do we balance the support for such campaigns by others now living that way and evidence that fear of

public shame and personal remorse works to deter both?”

Phelan: I question nearly every part of this (implied) argument. First, why should seeing the gore of traumatic

injuries upset only those bearing their possible effects? I am neither an intoxicated driver nor quadriplegic, and I

certainly do not wish to see traumatic open fractures, evisceration, amputations, blood, or human remains, much less support

their display on billboards or posters in public. My descriptions here might be criticized as exaggerated, but note that

Chapman specifically employs “vivid…carnage and misery” in his rhetoric. Second, why should our question of interest be the

balance of (i) victims’ support for FMC and (ii) evidence of FMC’s efficacy? Why focus on these two factors in particular?

Victims of drunk drivers might (quite likely) constitute a minority of those with an interest in the policy choice to adopt

FMC (e.g. all potential victims), and the question of FMC’s efficacy is but a single dimension of a consequentialist

assessment of its ethicality. Third, why should the result of engendering “fear of public shame or personal remorse” be

employed as a specific benefit of FMC as described? Why should we favor gruesome imagery for achieving these ends

over, for example, public display of the names and faces of offenders? This particular alternative seems both more relevant

and more targeted toward the ends for which evidence is ascribed.

Chapman: “if ghoulish pack warning illustrations of tobacco-caused disease like gangrene and throat cancer render the

damage of smoking far more meaningful than more genteel explanations, whose interests are served by decrying such depictions

as being somehow unethically disturbing?”

Phelan: Chapman’s question is undoubtedly intended as rhetorical, but an earnest answer should be considered: the

interests served are those of the individuals who would be harmed by exposure to such “ghoulish” and “disturbing” imagery.

This is not an obscure conclusion to offer in response, but Chapman’s rhetorical phrasing suggests that there are no

interests served by restraint in public messaging (provided it offers at least some potential benefit). It is these

interests that must be weighed against the interests of those who might benefit from FMC, whether the individuals targeted

or those who might benefit collaterally.

Fear or Foul?

Chapman appears to conflate two very different ideas with regard to FMC: one is the very concept of challenging culturally

held or commercially promoted values and norms of deleterious health behaviors, and the other is the specific means of doing

so through extreme, graphic imagery. This is odd, because Fairchild and colleagues make the distinction explicitly:

A fear-based appeal need not make populations quake with anxiety or recoil in disgust when faced with gruesome images of death or disfigurement. Rather, fear-based messaging, whether an image or narrative, can make a threat feel immediate and make target audiences feel vulnerable.

This seems quite reasonable, for why should fear require offense?

Fairchild et al. later say,

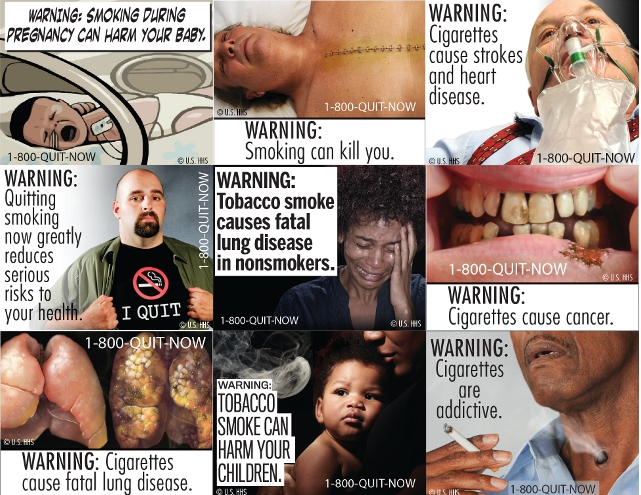

…nothing more tellingly reveals the embrace of fear and gore in the public health response to smoking than the graphic tobacco warnings that the US Food and Drug Administration sought to place on cigarette packages.

This really piqued my interest, given that I had never seen any graphic warning labels of this sort (though as Fairchild et

al. note, the proposed images were ever employed in product labeling). Upon locating the proposed images (apparently

courtesy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services), I was underwhelmed:

Fear? Sure. Gore? Not so much. The closest examples are the obviously Photoshopped images of a tracheostomy and a

lip ulcer; neither the seemingly-CG images of healthy and diseased lungs nor the stapled-shut median sternotomy incision

seem particularly gory to me. Initially I thought I might be underrating these images, but comparison with the graphic

warnings apparently used in Brazil dispelled that thought. I will describe them below but won’t display them (the images

can viewed through this link, hosted

by the Kansas Health Institute).

These seven of the ten total images I would describe as presenting variable degrees of gore, all of which are more intense

than any of the HHS images. Comparison of the chest incision images reveals the difference very clearly, as the HHS image

looks generally like a living human, whereas the Brazil image truly looks like a cadaver in a morgue. Both sets of images

might provoke fear, but I would expect the Brazilian images to provoke rather strong feelings of disgust as well, and I would

not be surprised if many in the lay public found them quite disturbing. I doubt such feelings would be anywhere near as

common in response to the HHS images.

My general thought in comparing the two sets of images is that the Brazilian images are more extreme than necessary, specifically to the extent that they depict gore. It is interesting to consider the remaining Brazilian images, some of which I think would provoke fear (but not disgust) rather effectively:

I have to conclude that Fairchild and colleagues are correct, that it is simply not necessary for fear-based messaging,

even of the visual (graphic) sort, to incorporate gruesome images with shock value. It it curious that Chapman focuses so

much on justifying this component, especially when the authors of his target article take a different tack.

Dimensions of Ethical Analysis

Specific FMC criticisms aside, two aspects of deliberation appear neglected in Chapman’s discussion. The first relates to

question framing, and the second to context.

Seeking to answer a yes-no question of the sort, “Is this action (un)ethical?” often betrays a value judgment that the

action in question necessarily falls into either of the two categories without ambiguity. Such questions do not

necessarily reflect such value judgments, but my reading of Chapman suggests that he treats the question as a

dichotomous one (his absolutism in presenting the alleged criticisms of FMC is but one example). Of course, many such

judgments of ethical quality reflect nuanced differences in the actions under consideration, and cannot be legitimately

dichotomized into “good” and “bad” categories.

The second issue follows from this, and concerns the fact that ethical decision-making requires more than comprehensive

evaluation of the morally significant characteristics of a potential course of action. Specifically, determining the most

ethical course requires assessment of comparative ethicality, where the merits and demerits of the alternatives

must be considered in context against one another.

What are several implications of these issues for debating the ethicality of FMC? First, ethical assessments should not be

constrained by false dichotomies, but should strive to fully and clearly identify and evaluate the morally significant

aspects essential to FMC. Second, if a dichotomous judgment is asserted, it must be recognized that it is not enough

for FMC to be deemed “ethical” (for example). For employment of FMC to be defensibly judged as “ethical,” it ought to be

not substantially worse (on balance) than any similarly feasible alternative. This idea is captured within the

principlist ethical framework by the principle of proportionality. Thus, even if entangling gore with messaging is

not clearly “unethical,” it must still be justified over alternatives.

Conclusions

In praising Fairchild and colleagues for their insight, Chapman accuses the field of public health of “confused thinking”

on fear-based messaging. On a critical reading, I am afraid Chapman may be guilty of the very fault he denounces, though I

certainly agree that the role of fear in public health messaging “deserves wide discussion.” What is absent from Chapman’s

commentary but discussed extensively by Fairchild et al. is the role and reception of stigma derived from public health

messaging campaigns—I may return to this for discussion in the future.